In Your Community

Creating Net-Positive Communities: GAF Taking Action to Drive Carbon Reduction

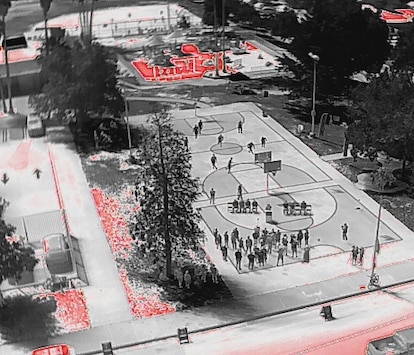

Companies, organizations, and firms working in the building, construction, and design space have a unique opportunity and responsibility. Collectively, we are contributing to nearly 40% of energy-related carbon emissions worldwide. While the goals, commitments, pledges, and promises around these challenges are a step in the right direction, no one entity alone will make major improvements to this daunting issue.We need to come together, demonstrate courageous change leadership, and take collective approaches to address the built environment's impacts on climate. Collectively, we have a unique opportunity to improve people's lives and make positive, measurable changes to impact:Buildings, homes, and hardscapesCommunity planningConsumer, commercial, and public sector behaviorOur Collective Challenge to Reduce our Carbon FootprintAccording to many sources, including the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), the built environment accounts for 39% of global energy-related carbon emissions worldwide. Operational emissions from buildings make up 28% and the remaining 11% comes from materials and construction.By definition, embodied carbon is emitted by the manufacture, transport, and installation of construction materials, and operational carbon typically results from heating, cooling, electrical use, and waste disposal of a building. Embodied carbon emissions are set during construction. This 11% of carbon attributed to the building materials and construction sector is something each company could impact individually based on manufacturing processes and material selection.The more significant 28% of carbon emissions from the built environment is produced through the daily operations of buildings. This is a dynamic that no company can influence alone. Improving the energy performance of existing and new buildings is a must, as it accounts for between 60–80% of greenhouse gas emissions from the building and construction sector. Improving energy sources for buildings, and increasing energy efficiency in the buildings' envelope and operating systems are all necessary for future carbon and economic performance.Why It Is Imperative to Reduce our Carbon Emissions TodayThere are numerous collectives that are driving awareness, understanding, and action at the governmental and organizational levels, largely inspired by the Paris Agreement enacted at the United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP21) in 2015. The Architecture 2030 Challenge was inspired by the Paris Agreement and seeks to reduce climate impacts from carbon in the built environment.Since the enactment of the Paris Agreement and Architecture 2030 Challenge, myopic approaches to addressing carbon have prevailed, including the rampant net-zero carbon goals for individual companies, firms, and building projects. Though these efforts are admirable, many lack real roadmaps to achieve these goals. In light of this, the US Security and Exchange Commission has issued requirements for companies, firms, and others to divulge plans to meet these lofty goals and ultimately report to the government on progress in reaching targets. These individual actions will only take us so far.Additionally, the regulatory environment continues to evolve and drive change. If we consider the legislative activity in Europe, which frequently leads the way for the rest of the world, we can all expect carbon taxes to become the standard. There are currently 15 proposed bills that would implement a price on carbon dioxide emissions. Several states have introduced carbon pricing schemes that cover emissions within their territory, including California, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. Currently, these schemes primarily rely on cap and trade programs within the power sector. It is not a matter of if but when carbon taxes will become a reality in the US.Theory of ChangeClimate issues are immediate and immense. Our industry is so interdependent that we can't have one sector delivering amazing results while another is idle. Making changes and improvements requires an effort bigger than any one organization could manage. Working together, we can share resources and ideas in new ways. We can create advantages and efficiencies in shared R&D, supply chain, manufacturing, transportation, design, installation, and more.Collaboration will bring measurable near-term positive change that would enable buildings and homes to become net-positive beacons for their surrounding communities. We can create a network where each building/home has a positive multiplier effect. The network is then compounded by linking to other elements that contribute to a community's overall carbon footprint.Proof of Concept: GAF Cool Community ProjectAn estimated 85% of Americans, around 280 million people, live in metropolitan areas. As the climate continues to change, many urban areas are experiencing extreme heat or a "heat island effect." Not only is excess heat uncomfortable, but heat islands are public health and economic concerns, especially for vulnerable communities that are often most impacted.Pacoima, a neighborhood in Los Angeles, was selected by a consortium of partners as a key community to develop a first-of-its-kind community-wide research initiative to understand the impacts various cooling solutions have on urban heat and livability. Pacoima is a lower income community in one of the hottest areas in the greater Los Angeles area. The neighborhood represents other communities that are disproportionately impacted by climate change and often underinvested in.Implementation:Phase 1: This included the application of GAF StreetBond® DuraShield cool, solar-reflective pavement coatings on all ground-level hard surfaces, including neighborhood streets, crosswalks, basketball courts, parking lots, and playgrounds. The project also includes a robust community engagement process to support local involvement in the project, measure qualitative and quantitative impact on how cooling improves living conditions, and ensure the success of the project.Phase 2: After 12 months of monitoring and research, GAF and partners will evaluate the impact of the cool pavements with the intent to scale the plan to include reflective roofing and solar solutions.This ongoing project will allow us to evaluate for proof of concept and assess a variety of solutions as well as how different interventions can work together effectively (i.e., increasing tree canopies, greenspacing, cool pavements, cool roofs, etc.). Through community-wide approaches such as this, it's possible that we could get ahead of the legislation and make significant innovative contributions to communities locally, nationally, and globally.GAF Is Taking Action to Create Community-wide Climate SolutionsWith collaboration from leaders across the building space and adjacent sectors, we believe it is possible to drive a priority shift from net neutral to net positive. Addressing both embodied and operational carbon can help build real-world, net-positive communities.We invite all who are able and interested in working together in the following ways:Join a consortium of individuals, organizations, and companies to identify and develop opportunities and solutions for collective action in the built environment. The group will answer questions about how to improve the carbon impacts of the existing and future built environment through scalable, practical, and nimble approaches. Solutions could range from unique design concepts to materials, applications, testing, and measurement so we can operationalize solutions across the built environment.Help to scale the Cool Community project that was started in Pacoima. This can be done by joining in with a collaborative and collective approach to climate adaptation for Phase 2 in Pacoima and other cities around the country where similar work is beginning.Collaborate in designing and building scientific approaches to determine effective carbon avoidance—or reduction—efforts that are scalable to create net-positive carbon communities. Explore efforts to use climate adaptation and community cooling approaches (i.e., design solutions, roofing and pavement solutions, improved building envelope technologies, green spacing, tree coverage, and shading opportunities) to increase albedo of hard surfaces. Improve energy efficiency to existing buildings and homes and ultimately reduce carbon at the community level.To learn more and to engage in any of these efforts, please reach out to us at sustainability@gaf.com.

By Authors Jennifer Keegan

May 31, 2023